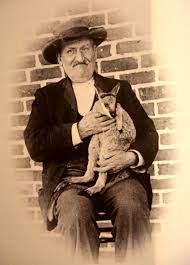

HISLOP, James John Henry ( 1824-1909 ) – Convict 530.

‘Western Australian Convict, First Bond Schoolmaster, Clerk, Bunbury Businessman’.

James HISLOP was born on October 21, 1824 in Edinburgh, Scotland to parents James HISLOP and Allison LYDELL. Little is known of his parents, or whether or not he had any siblings, but James wrote in 1849 that his parents were respectable people living in the south of Scotland. During his youth, James was bound to a notary and law writer, serving an apprenticeship for four years and he became a very well educated and able clerk. On completion of his four years, he obtained several good situations, but gained a reputation as a somewhat unreliable employee.

By 1846, when he was 22 years of age, James had joined the British army and was a recruit in the 50th Queen’s Own Regiment of Foot stationed at Chatham, England. He was transferred to Walmer in 1848, promoted to the rank of sergeant and was serving as the paymasters’ clerk. All seemed to be going well, but late in 1848, it appears that James had reverted to those same loose habits he exhibited in Edinburgh. He owed money in the town and his solution was to steal military medals from the paymaster. The 50th Queens’ Own had an exemplary reputation in overseas campaigns and its members accumulated several medals while on service. Some men never returned to Britain to collect their medals; it was those medals that James stole.

In November 1848, James was arrested by the civil authorities and incarcerated at Dover on a charge of felony. His case came to trial on 8th January 1849. On pleading guilty to stealing medals to the value of £32 from Regimental Paymaster Lieutenant John Beach DODD, he was found so, sentenced to seven years transportation and immediately returned to Dover Prison. Five months later, on 1st May 1849, he was transferred to Millbank Prison, convict number 17293, aged 23, single, superior read and write, soldier, dissenter. Millbank prisoners lived in a totally controlled environment of isolation. Conversation or contact with fellow prisoners was strictly forbidden, a treatment that was expected to produce a reformed individual. After seven months at the relatively clean and quiet Millbank Prison, James was transferred to the Stirling Castle prison hulk. Hulks were de-commissioned ships moored in the Thames River. Most prisoners who had been sentenced to transportation spent some time on a hulk, where an atmosphere of misery and decay pervaded. The ships were uncomfortable and disease ridden, but prisoners did have a better diet and were employed on public works ashore.

A little over a year later, on 10 March 1851, James was transferred to the transport ship Pyrenees for the three month voyage to Western Australia. Surgeon Superintendent MACLEROY, who was in charge of the prisoners’ health and well-being on the voyage, reported that there was little sickness and the convicts exhibited highly satisfactory behaviour and were generally cheerful and obedient. The Pyrenees arrived at Fremantle on 28th June 1851, the fourth transport to arrive. James became Convict No. 530, age 26, clerk, single, and had no children. His physical description was recorded as five foot, six and a half inches tall; dark brown hair, hazel eyes, oval face, dark complexion, slight build and his distinguishing feature was a hairy breast.

Practically all the convicts aboard the Pyrenees, including James, were eligible for immediate ticket-of-leave on arrival, that is, they were not imprisoned, but able to live in the community and choose an employer, or work for themselves. However, accommodation ashore was scarce and a party of about forty men who were selected to travel on to Bunbury, were kept on board Pyrenees until late in July when they were transferred to the John Panter for the trip to Bunbury.

Bunbury was situated 100 miles (170 kilometres) south of Fremantle on the coast at Koombana Bay. It was an isolated village confined on a peninsular below scrub covered sand hills in the Wellington District, which had a population of about 300 European people at the time, a very different circumstance to that of the bustling cities of Scotland and England. James and his fellow ticket-of-leavers settled in at the convict depot. Until employment was offered by the settlers, the convicts were employed on public works and supported at the depot. James began life in Bunbury at the depot and on public works, the main project at the time being the construction of the Bunbury to Perth road.

About a month later, on 15th September, James was appointed to the position of schoolmaster at the Government Boys School. He had the distinction of being the first convict appointed as a schoolmaster. He had no teaching experience but was well educated. Trained teachers were not attracted to the colony. The pay was low and free men were not generally interested in the profession. The Board of Education was reluctant to employ convict teachers and, probably, the deciding factor in James’ employment was that the parents of the children supported him. His pupils included those from the ruling families in the town and the sons of William FORREST, John (later Sir John), Alexander (later Mayor of Perth) and David, (north-west pioneer grazier). James soon became known for his quiet, very even temper and willingness to help. He gained a little respectability from the position and although the pay was low, it was well above the wage paid to ticket-of-leave labourers.

In October 1853, James married Bridget MULQUEEN, who arrived in the colony in January 1853, escaping the Great Hunger, the 1845-52 Irish famine. James remained in his position as schoolmaster and when, in 1854, girls were permitted to attend the school he was instrumental in gaining the services of his wife to teach sewing and knitting to the girls. But, even though James was a successful teacher, the Board of Education felt that he was not the ideal schoolmaster; they let it be known that they would prefer a free, trained teacher.

On 7th January 1856, James officially became a free man, his sentence served. In reality, he became an expiree. When convicts arrived in Western Australia a new class was established in a very class conscious society. Convicts fell to the bottom rung. Expirees remained there. Expiree teachers were dismissed as frequently as convict teachers, so it was quite extraordinary and a tribute to James that he held his position for so long. In November 1861, an attempt was made to have James arrested for issuing a cheque when he had no funds to cover it. Although the charge was false, and no arrest made, gossip laid the seed of impropriety. Around the same time, James was embroiled in another incident while acting as an agent for Edward HESTER, a farmer who had retired as a storekeeper in Bunbury. James was employed by HESTER to collect money owed to him. The case went to court in July 1862. James pleaded not guilty and was found so. The Board of Education dismissed James for improper conduct and neglect in the discharge of his duties. A free teacher, George Teede Jnr was appointed schoolmaster at Bunbury on the same day. Both cases brought against James had weak foundations and he was found not guilty, but he never regained his position as schoolmaster.

James and Bridget had a family of five children now. To support them, James took employment as a pull away hand, operating the oars of a whaling boat in Joseph BUSWELL’S whale fishery at Bunbury and Minninup for the 1862 season. It was hard, physical work, but he only worked one season. By 1863, he found employment with Henry YELVERTON at his timber mill at Quindalup as a clerk. The family moved there and lived in the little self-contained mill village in a two roomed cottage, with boarded walls, a shingle roof and a lean-to addition. The timber industry was a boom or bust operation and the Hislop family did not stay. They returned to Bunbury around 1869.

James soon found employment as an accountant with W Spencer & Sons at the Wellington Store. Over the next years, James remained an accountant and clerk and worked for William SPENCER and on his own account at times. He was appointed auditor to the Bunbury Municipal Council for 1878 and ten years later was elected a councillor. During the 1880s, James was a wharfinger. In 1882, he won the tender for trucking on the Bunbury jetty and owned two boats, the gig Pinafore and the lighter Enterprise. Without a customs license, his activities were confined to Bunbury. Sons William and James worked the boats with their good friend Teddy WITHERS. They also took part in regattas and had some success. In 1885 James became an agent for the National Mutual Life Association with a glowing reference from William SPENCER supporting his application.

In 1886, James had a career change. John FIELDING, the owner of the Prince of Wales Hotel in Stephen Street, Bunbury prepared to leave the colony and sold his hotel to Charles WISBEY, who was the licensee of the Wellington Hotel. Because he was tied to the Wellington Hotel, WISBEY put James HISLOP in charge at the Prince of Wales, with James taking over the license on 17 March 1886. However, WISBEY wanted to take over his new purchase in January, 1887 so James applied for and was granted the lease and the licence of the Wellington Hotel for that year. With family help, James ran the Wellington for three years. Then, in January 1890, he defaulted on a payment to Tolley & Co., Wine, Spirit and General Merchants of Fremantle, and this led to James’ application for liquidation under the Bankruptcy Act. James was able to sell his interest in the hotel as a going concern, but the family, who had lived at the hotel, were forced to leave.

John HANDS had recently built a large house of eleven rooms on Wollaston Street and the HISLOP family took the lease and moved in. Here, they established a private boarding house they named Bellevue Villa, commonly known as Hislops’ Boarding House. Son Harry held the license, and Bridget, with the reputation of her ‘golden opinions’ bestowed upon her at the Wellington Hotel, ran the house. With the gold boom of the 1890s, Bunbury gained a reputation as a seaside resort and boarding and lodging houses were in demand. In 1894 son James Jnr. and his wife Eliza built Beach House, a ten room, two bathroom custom-built boarding house on the corner of Wollaston Street and Koombana Terrace, Bunbury as an investment and his parents moved in to run it. The hospitality industry suited the Hislop family. Beach House gained in reputation and became Bunbury’s best known and most popular resort for locals and holiday makers alike.

Bridget HISLOP died on 3rd April 1907 at Beach House. After her death, James remained at Beach House with the support of his daughters until he died there on 23rd October 1909, surrounded by family, aged 85 years. Both Bridget and James were buried in the old Bunbury Cemetery, now Pioneer Park. On hearing of the death of James, Sir John FORREST sent a telegram regretting that he could not be present at the funeral of one he always regarded as one of his truest friends.

Together, James and Bridget HISLOP overcame the difficulties of being a convict and an Irish Catholic servant woman and raised their family of ten children in Western Australia. Over the years, James always had a ready pen to assist the illiterate pioneers; some say he wrote over 1,000 letters for the old immigrants. He died a well-loved and respected gentleman. James never returned to Edinburgh, although he always called himself an Edinburgh man.

James told the family why he came to Western Australia:

I was in the army and my battalion was about to be sent to India. I did not want to go, so I left the army and came to Western Australia.

Another version:

I was in the army. One day an Officer made a disparaging remark about a lady I knew. I hit him and was dismissed from the army. I left home and came to Western Australia.

Written by

LORNA CROSS

14 March, 2021.

REFERENCES:-

Cross, Lorna. I’m an Edinburgh Man; James John Henry Hislop (1824-1909), 2011, Self Published.

Available from Lorna Cross $20 per copy plus postage: lornaacross@hotmail.com